Brad Rubin, Sector Manager, Specialty Crops, Wells Fargo Agri-Food Institute

As the largest agricultural state in the U.S., producing over $58 billion in crop receipts across numerous commodities, California’s agriculture is bountiful. More than 33% of the nation’s vegetables and approximately 75% of the nation’s fruits and nuts are grown in California. And farmers, focused on efficient growing, stronger yields, and reduced costs, are doing their part to make healthy, fresh foods more affordable. This is certainly welcome news to American consumers who have grown wary of ongoing food inflation in the grocery aisles.

As the largest agricultural state in the U.S., producing over $58 billion in crop receipts across numerous commodities, California’s agriculture is bountiful. More than 33% of the nation’s vegetables and approximately 75% of the nation’s fruits and nuts are grown in California. And farmers, focused on efficient growing, stronger yields, and reduced costs, are doing their part to make healthy, fresh foods more affordable. This is certainly welcome news to American consumers who have grown wary of ongoing food inflation in the grocery aisles.

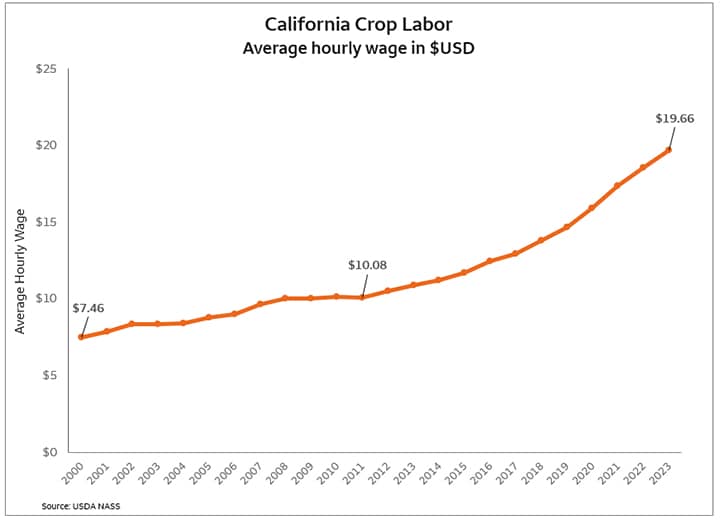

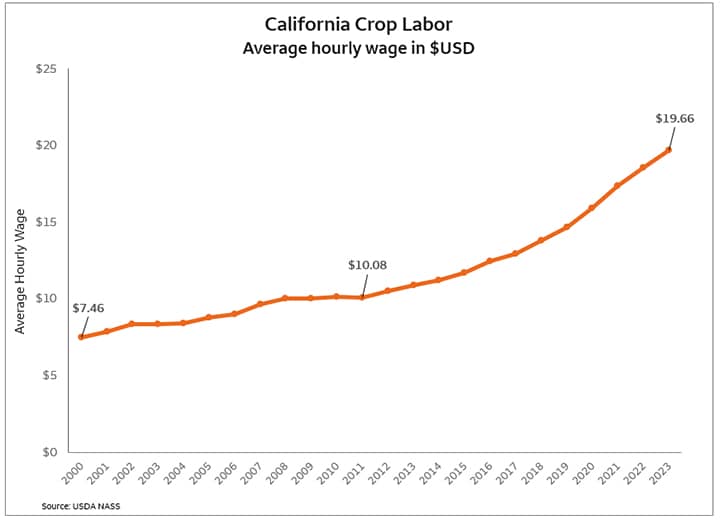

There are two major concerns for growing food in California – water and labor. Both present challenges specific to availability and cost. While Mother Nature has provided recent relief on water availability, farmers remain challenged by labor shortages and rising labor costs. Advancements in technology and automation are creating opportunities to improve efficiencies while providing some relief for labor issues, and ideally, this results in fewer instances of farmers having to pass rising costs onto consumers.

On January 1, 2024, California’s minimum wage increased to $16 per hour, and in November, California will vote on another increase to $18 per hour, the highest proposed minimum wage in the U.S. Truth be told, California farmers need to pay more for labor integral to running their businesses since it is not uncommon to see labor costs at $20 per hour for farmworkers. Other less labor intensive industries, pay higher minimum wages. For example, quick-service restaurants with more than 60 locations are now required to pay employees $20 per hour in California. Bottom line, California’s labor market has become more competitive than ever, and farmers are faced with paying higher wages to hire and retain workers.

In addition to rising labor costs, California farmers also struggle with labor availability. There is not enough farm labor available to support the massive number of commodities produced in the state. Government run programs like H-2A provide some relief, creating a path for farmers to hire seasonal foreign workers to offset the labor shortage. However, the program requires farmers to make investments in housing and transportation in addition to paying the prevailing minimum wage. The costs and/or ability to provide housing can present additional challenges for farmers. Many agricultural subsectors such as berries have made the H-2A program work out of necessity, since hand picking is still required by berry growers to avoid damage to the fruit. It’s important for California to continue to find ways of securing labor and mitigating the high cost of running operations.

The above said, the economic tail winds of healthy eating are helping the California Ag economy. For health-conscious Americans, salads are an everyday meal. In 2023, California produced 78% of all head, leaf, and romaine lettuce in the U.S., while Arizona produced the remaining 22%. For price-sensitive consumers healthy eating has become increasingly expensive and labor costs are one of the main drivers for the increased cost of lettuce and bagged salads in grocery stores. So, farmers are being challenged to become more creative with reduction in labor needs and costs.

As one answer, technological advances in field and plant automation are starting to make more economic sense for producing crops in California. An example of technology utilized by large-scale farming operations growing specialty crops is the LaserWeeder, a tractor implement made by Carbon Robotics that uses lasers to identify and burn weeds before they can infiltrate and compete for production crop resources. The machines are built with 24 Nvidia GPUs and 42 HD cameras for AI learning, and are equipped with a 20 foot boom that can mitigate weeds across multiple rows at one time. LED strobe lights on the boom provide the correct environment for the camera operations to first predict which weeds are invasive and then target cameras to precisely align a laser to zap them. The 150-watt CO2 lasers have precision accuracy to less than a millimeter and can be adjusted to fit into crop rows. Importantly, the AI software, powered by the Nvidia processors, ensures that the lasers do not touch or strike production crops in the ground. So, because the LaserWeeder can kill weeds before they become visible to the human eye, it automates a grueling task and helps to offset labor challenges.

An added advantage of technology is that it can facilitate a more-organic growing process by reducing the need for herbicides. In the example of the LaserWeeder, the weeding process can be more effective than herbicides on both yields and quality since it is a no-touch, organic method that doesn’t harm crops, nor stir the ground. New weed seeds are less likely to geminate if the ground is not stirred, meaning less passes or applications than conventional herbicides or mechanized weeding. So, while LaserWeeder machines are expensive, case studies demonstrate that payback occurs within one to three years in reduced labor and herbicide costs in addition to also improving yield and quality.

I had the opportunity to see the LaserWeeder in action, and it was both a spectacle and a treat. While you can’t see the lasers off the boom, you can smell and see the remnants of burned weeds as it passes over crops. It is a remarkable piece of equipment that makes weeding efficient and less invasive.

California farmers are truly working to feed America. In attempt to keep food costs reasonable, more and more farmers are turning to technology to create efficiencies. Some industries can automate faster than others, but as technology evolves, machine vision and learning will continue to follow the exponential growth curve. This, combined with falling capital costs, will continue to create opportunity for additional automation in the fields and packing houses. So, while we can’t effectively automate berry picking today, growers of other specialty crops, like onions and lettuce, are embracing and adopting new technologies that can solve for labor challenges, improve yields, and help to produce more organic food.

Brad Rubin is the Sector Manager for Specialty Crops within Wells Fargo’s Agri-Food Institute, and focuses on fruits and vegetables. Brad joined Wells Fargo in January 2018, having formerly worked as Chief Marketing Officer for iD Tech. Prior, he was Vice President of Operations for Kibo Commerce, an enterprise e-commerce provider. Before Kibo Commerce, Brad served as the Director of Global Operations at TransUnion and managed customer operations globally for the credit bureau’s direct-to-consumer business.

Brad Rubin is the Sector Manager for Specialty Crops within Wells Fargo’s Agri-Food Institute, and focuses on fruits and vegetables. Brad joined Wells Fargo in January 2018, having formerly worked as Chief Marketing Officer for iD Tech. Prior, he was Vice President of Operations for Kibo Commerce, an enterprise e-commerce provider. Before Kibo Commerce, Brad served as the Director of Global Operations at TransUnion and managed customer operations globally for the credit bureau’s direct-to-consumer business.

Brad holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Industrial Technology from California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo.

Sign On

Sign On  As the largest agricultural state in the U.S., producing over $58 billion in crop receipts across numerous commodities, California’s agriculture is bountiful. More than 33% of the nation’s vegetables and approximately 75% of the nation’s fruits and nuts are grown in California. And farmers, focused on efficient growing, stronger yields, and reduced costs, are doing their part to make healthy, fresh foods more affordable. This is certainly welcome news to American consumers who have grown wary of ongoing food inflation in the grocery aisles.

As the largest agricultural state in the U.S., producing over $58 billion in crop receipts across numerous commodities, California’s agriculture is bountiful. More than 33% of the nation’s vegetables and approximately 75% of the nation’s fruits and nuts are grown in California. And farmers, focused on efficient growing, stronger yields, and reduced costs, are doing their part to make healthy, fresh foods more affordable. This is certainly welcome news to American consumers who have grown wary of ongoing food inflation in the grocery aisles.

Brad Rubin is the Sector Manager for Specialty Crops within Wells Fargo’s Agri-Food Institute, and focuses on fruits and vegetables. Brad joined Wells Fargo in January 2018, having formerly worked as Chief Marketing Officer for iD Tech. Prior, he was Vice President of Operations for Kibo Commerce, an enterprise e-commerce provider. Before Kibo Commerce, Brad served as the Director of Global Operations at TransUnion and managed customer operations globally for the credit bureau’s direct-to-consumer business.

Brad Rubin is the Sector Manager for Specialty Crops within Wells Fargo’s Agri-Food Institute, and focuses on fruits and vegetables. Brad joined Wells Fargo in January 2018, having formerly worked as Chief Marketing Officer for iD Tech. Prior, he was Vice President of Operations for Kibo Commerce, an enterprise e-commerce provider. Before Kibo Commerce, Brad served as the Director of Global Operations at TransUnion and managed customer operations globally for the credit bureau’s direct-to-consumer business.